Introduction

The Age-old method involves brushing first and then breakfast next. The basic approach is that to prevent the toxins of bad bacteria ( Anaerobic bacteria ) present in the mouth entering into digestive tract along with the food and causing various inflammatory diseases in the body.

Essentially, the human oral cavity harbours over 700 distinct types of microorganisms, forming one of the most diverse and complex microbial ecosystems in the body — the oral microbiota. While traditionally associated with dental health, emerging evidence now links these oral microbes to a range of systemic inflammatory diseases, particularly those affecting the gut, cardiovascular system, and other organs.

As medical understanding of the oral-gut axis grows, it’s becoming increasingly clear that oral bacteria are not confined to the mouth. They can migrate through saliva and bloodstream, disrupting microbial balance in distant parts of the body and contributing to chronic inflammation and disease development.

This article explores how oral microbiota influence systemic health, with a focus on gut health and broader implications for inflammatory diseases.

Oral Bacteria and Gut Health How Do Oral Bacteria Reach the Gut?

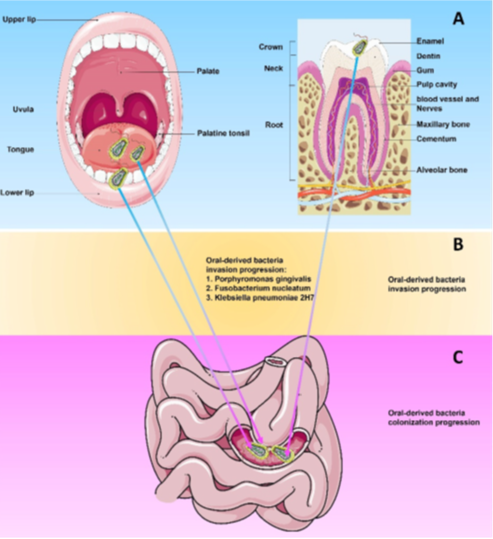

Recent research shows that oral-derived bacteria can enter the gastrointestinal (GI) tract through swallowed saliva — an event that happens nearly 1.5 liters per day. Once in the gut, these bacteria can either:

- Directly colonize the gut lining, especially when the native gut microbiota is compromised, or

- Indirectly affect gut health by altering the immune response, disrupting the mucosal barrier, or influencing inflammatory signaling.

- A. Basic Structure of Oral Cavity: Demonstrates the rich and complex microbial network present in the mouth

- B. Bacterial Invasion: Illustrates how oral microbes enter and move through the digestive tract.

- C. Colonization Process: Highlights how these microbes establish themselves in the gut and affect native microbiota

This process is especially dangerous in conditions where the gut microbiota is imbalanced (dysbiosis), such as in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or after antibiotic therapy.

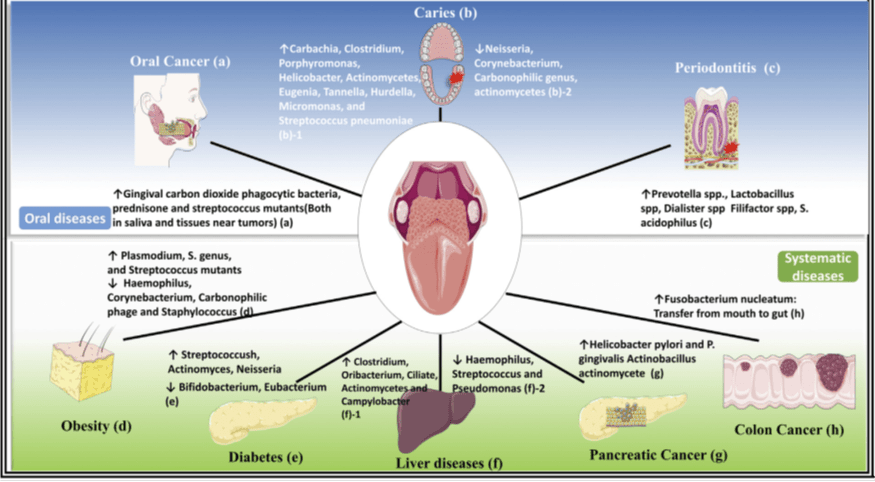

Oral Microbiota and Systemic Inflammatory Diseases

Oral bacteria do not stop at the gut. Scientific studies have demonstrated links between oral pathogens and a host of systemic diseases, many of which have inflammatory or autoimmune components.

Diseases Linked to Oral Microbiota

- Cardiovascular disease (CVD): Oral pathogens like Porphyromonas gingivalis have been found in atherosclerotic plaques.

- Diabetes mellitus: Chronic oral inflammation increases insulin resistance.

- Rheumatoid arthritis (RA): Molecular mimicry from oral bacteria may trigger autoimmune reactions.

- Alzheimer’s disease: Evidence suggests P. gingivalis and its toxic proteins may contribute to neuroinflammation.

- Respiratory infections: Inhaled oral bacteria can cause or worsen pneumonia.

- Colorectal cancer: Oral microbes like Fusobacterium nucleatum are frequently detected in colorectal tumors.

Clinical Implications and Preventive Strategies

As we learn more about the oral-systemic connection, it becomes crucial for healthcare professionals — not just dentists — to emphasize oral hygiene as a gateway to overall health.

Preventive Recommendations:

- Regular dental check-ups: Essential for identifying and treating oral infections early.

- Good oral hygiene: Daily brushing, flossing, and use of antimicrobial mouthwashes can reduce harmful bacteria.

- Good oral hygiene: Daily brushing, flossing, and use of antimicrobial mouthwashes can reduce harmful bacteria.

- Dietary interventions: Reducing sugar intake and eating fiber-rich foods promote a balanced oral and gut microbiota

- Probiotic therapies: Emerging evidence suggests that certain probiotics may help modulate oral and gut microbial communities.

- Systemic screening: Patients with chronic inflammatory diseases should be screened for periodontal disease and other oral infections.

Conclusion

The mouth is no longer viewed as an isolated system; it is a critical entry point to the body’s overall health. Understanding and managing oral microbiota is essential not only for dental care but also for preventing and managing systemic diseases.

Incorporating this knowledge into medical practice opens up new preventive and therapeutic avenues — reinforcing the importance of a multi-disciplinary approach to patient care.